Three years ago I was a newly arrived refugee in the UK, on the verge of losing my largely US-funded job because my US vetting had been held for almost a year without any response.

Vetting is the process of performing a background check on someone to approve paying them, however, the vetting applied by the organisations funded by the American State Department mainly involves checking for any ‘terror’ relations.

With the non-US funding I was receiving coming to a close, and my project due to become funded solely by the US, I was freaking out. I applied for every job I found online, even those I was overqualified for. London expenses, particularly when you are responsible for a kid, are no joke.

The vetting hassle was finally resolved when a friend of mine who works for the State Department interfered and found out that I was in the clear and could get the privileged ‘vetted ID’ needed to keep my job.

As a Syrian, such discriminatory acts are part of my daily life, and they have intensified since the uprising in 2011, which later turned into war.

For example, I am an internationally recognised journalist and human rights defender, yet the British government confiscated my Syrian passport because the Syrian regime reported it stolen. That was just a year before the vetting incident.

I am writing this to tell you that I know how vetting can easily be misused. It is a practice imbued with white superiority and privilege, led by prejudice, that is above all shallow.

I believe we need another kind of vetting for international and the local staff working in the Global South.

Why? This is what I will try to explain.

Human rights vetting

The US and EU vetting systems clear people of any ‘terrorism’ and criminal associations. But they cannot check whether those being vetted have undertaken activities that violate basic human rights, which are sometimes legal in some local communities.

Take the Middle East and North Africa for example, where child marriage, domestic violence, marital rape and sexual harassment are not criminalised in many countries. Your vetted director, who you have employed to lead an educational program, could be married to a 16-year-old girl. A director who has been hired to implement a project on gender-based violence, could be enslaving a trafficked woman from the Philippines or Ethiopia under the Kafala (sponsorship) system.

This system gives private citizens and companies in Jordan, Lebanon, and most Arab Gulf countries almost total control over migrant workers’ employment and immigration status. The lack of regulations and protections for migrant workers’ rights often results in low wages, poor working conditions and abuse.

Justifying not taking an action against a director who married a child or enslaved a trafficked domestic worker on the basis of it being ‘in their private life’ or not ‘directly related to the organisation’ is hypocrisy.

The personal is political, as we learned from second-wave feminists.

If you can violate human rights in your personal life, this will shape your political structures and the implementation of your organisation’s projects.

Over the past year, many international organisations have performed internal reviews to test the culture of white privilege following the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd. Do we have to wait until a wife is suffocated on camera by an international organisation’s staff member to start addressing how important human rights vetting is?

It’s true that such vetting is going to complicate the HR procedures, but it is worth it. Contacting the references given on a CV won’t indicate whether the candidate is abusive or whether they enslave a person.

Many companies worldwide are now using pre-hiring vetting to vet potential employees before making an offer to them, a procedure that could be applied by organisations, too, without violating any confidential information or breaking privacy laws.

Sovereignty of local projects

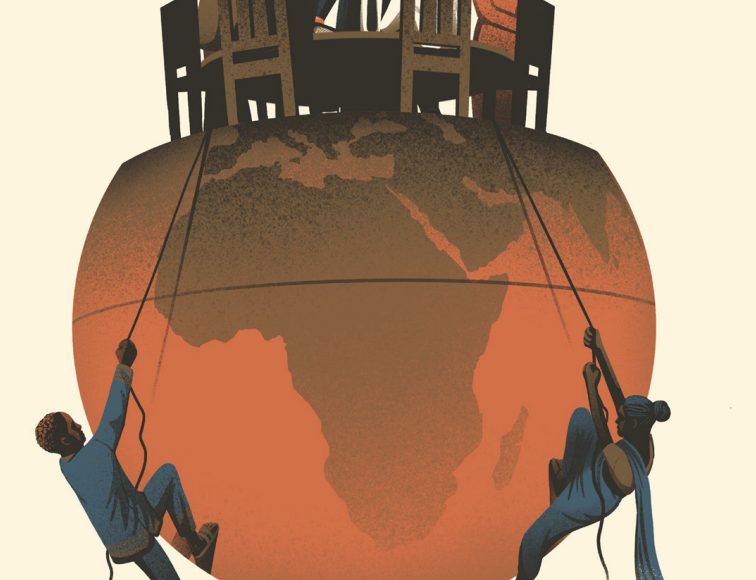

Another worthy review for international organisations is testing the dominance of a colonising mentality in the projects your organisation is implementing in the Global South.

Indicators could include how many local staff members are in decision-making positions; how much the company is willing to invest in helping those local staff to reach such positions; and local staff’s ownership of the projects funded in their country.

The more local platforms your organisation owns (both online and offline), the easier it will be to spot the dominance of the colonising mentality in your work.

For example, some international organisations working in Syria own local platforms, centres, Facebook pages, although they are supposed to be for locals, run by locals. When they find that the projects have impact and wide reach, the international organisations decide to own and use them for their next pitch for funding.

Instead of being given to the local group when the funding ends, some organisations keep these projects for themselves.

Supporting local projects to become independent and sustainable should be the success story every organisation writes about in its quarterly report. This would be more important than bragging about having a Facebook page with half a million local followers to get another fund and build another asset in your business chain.

I believe that decolonising the work of the international organisations should walk shoulder to shoulder with ‘de-businessing’ humanitarian work.

Without such measures and constant reviews and debates by the international organisations working in our regions, we won’t be able to work together to fight injustices, because we will “testifying in a court where the opponent is the judge”, as the Arabic proverb goes.

published on Open Democracy