In April 2013, I visited Raqqa for the first time in my life, a month after it was taken by anti-Assad rebel forces and nine months before it fell to Islamic State group (IS), who would use it as the base of their so-called ‘caliphate’.

Like my city Idlib, Raqqa had been systematically neglected by the Syrian government, its people faced what could be described as racism, and were known as “Shawaya“, or semi-sedentary, a term used pejoratively to imply naivety and simplicity.

My best friend Amer is Raqqawi, and we had been planning a trip to his hometown for more than a decade. While I was cautious about the stereotypical image of a rough, conservative, desert city, what I saw there shocked me.

Raqqa – at that time – was the first and only Syrian city where I have been able to combine my personal freedom with a political one. I wore the same clothes I bought in London, and walked, hair untied, in the market on my own, sitting in a public cafe, drinking mint lemonade, watching in disbelief as the women smoked shisha and Ahrar Alsham Islamists passed us by.

This was my feminist heaven compared to Aleppo and Idlib, where women were not so ‘liberated’ or present in public life.

In a cafe named Apple, I saw many old friends come to Raqqa from Beirut, Europe and even the US, to plan for projects and experience what Syria might be after the fall of the regime. Theatre, art, governance, human rights training were discussed in this small street cafe that closed at 3am. The whole city seemed not to sleep until dawn, despite the background sounds of mortars and scattered shootings.

About the first week of my visit, I wrote in my diary, “Astonishing Raqqawi women don’t walk close to walls, like women, including myself, do in our streets. Instead, they occupy the middle of the streets comfortably. They don’t look at the floor either, but into the eyes of others, even if they are armed foreign jihadists wearing Afghan-style clothing. Haven’t seen a blink of shyness, their clothes are modern and diverse, many of them are showing off their colourful hair in different styles while walking in the souk.”

Women were not just present in public spaces, in all the 50 civil society organisations and publications I counted then, more than half of their members were women of all ages and backgrounds, many leading the work. Zobaida Kharbotli, for example, was a leader and founder of Raqqa’s Local Coordination Committee, and the group “Jana” worked to support women and their role in society.

Raqqa at the time was a fascinating beehive of activity. We had high hopes, and finally seeing an alternative to the regime in action is what stays with me from that period.

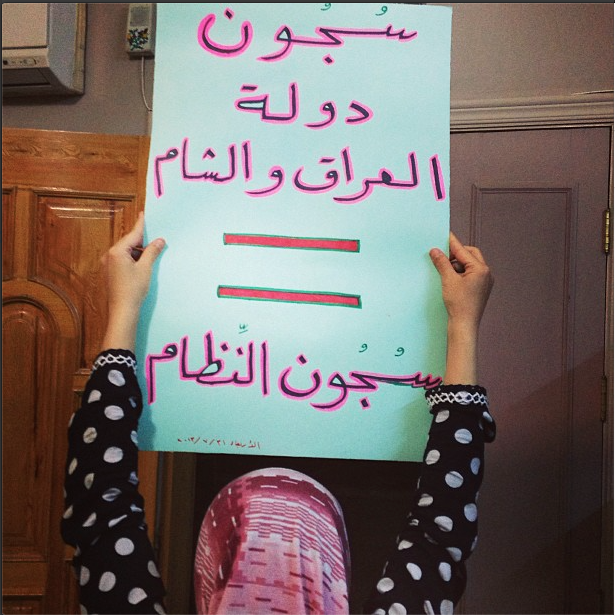

But when I visited again two months later, things were starting to become more tense; the number of jihadists increased, more black flags, IS activist kidnappings had also started, and with that, protests came back to the city.

But the Raqqawi women’s resistance was still visible to me. They smoked in the street in the middle of Ramadan, ignoring all the frowns of the armed men passing by.

I will never forget the time I was buying some stationary in front of Rasheed Park when I heard an armed jihadi telling an unveiled young woman “cover up sister, these clothes are not from Islam!” She looked at him firmly before responding “you turn your eyes away brother, otherwise I will shout out so loud that Boko Haram jihadists will hear me!”

My heart was pounding as I turned to help her in what I thought would develop into a fight, instead, the jihadi put his eyes back on the ground and walked away while muttering curses about the “out of control women”.

That evening in the Apple cafe, I saw many women in full make-up sitting with their male friends. As I looked at them in admiration a car stopped in front of us loudly playing the Amr Diab song El Alem Allah/God knows, followed directly by a pick-up truck drowning it out with the jihadist chant.

The next day as I attended my first mixed-gender media training, I heard an argument outside, and someone came in saying Ahrar al-Sham was outside investigating us. A man stood up and told the angry Islamist “brother, my daughter is attending this training, we have nothing to hide, it’s media training media.”

And when the Islamist asked him “how do you accept your daughter mixing with men?” He responded calmly, “I trust her, and those are my kids too, I am Dr Ismael Al Hamed, ask about me if you don’t know who I am.”

They left us in peace, but a couple of months later Dr Ismael was kidnapped by IS, and his whereabouts is still unknown.

Before leaving, I met Souad Nofal, a primary school teacher who started protesting on her own in front of

IS’s main headquarters every evening. I headed to the Palace of the Governorate to see her standing with a poster reading “No to kidnapping, no to stealing in the name of Islam”. Men passing by tried to avoid looking at her for fear of being considered as an ally.

“I started with a poster and here I am going back to it,” she told me, describing how she was using the same methods of protest she had against the regime, again with IS. Once she told an IS member who used to be her student “I didn’t teach you to become terrorist and kidnap those who disagree with you.”

After extensive and serious threats, Souad was forced to stop protesting and had to leave Syria. Many followed her in the coming months as IS became more dominant.

In December 2013 I visited Raqqa for the last time, just one month before IS completely took over. All the colours of the streets had been replaced with black, the organisations had disappeared, and cameras and filming were forbidden. It felt like the end of an era, and the beginning of an awful one.

As I was leaving the city, one last thing gave me a sense of hope: Unveiled women were still walking with confidence in front of the military bases with their colourful clothes, alone and in groups, one even had a fashionable hair bun. Some women in headscarves were heavily made up – their bright fuchsia lipstick clearly a sign of revolt against the blackness. I wrote on my Facebook that day that “toxic masculinity and manhood brought us weapons and ISIS, and it seems no one will get Syria back to us but the women”.

When Raqqa was liberated in the fall of 2017, its women took back their leading role. Some literally rebuilt their homes destroyed by regime coalition strikes, others restored their civil society organisations. Liberated from IS, the women of Raqqa faced a new challenge – preserving their independence and freedom under the Syrian Democratic Forces, a challenge they are still fighting today.